At the time, it felt like just another routine day at the office. I had returned from a hearty breakfast in the court cafeteria when I received an unexpected call from a former classmate of mine at the International University of Malaysia, Mr. Ahmed Hamza. He soberly informed me that security forces had ruthlessly beaten a prisoner to death, and that rioters were actively preventing the authorities from burying the body.

Knowing the potential gravity of the moment, I raced to the cemetery where the rioters had forced the authorities to abandon the battered and bruised body, leaving it on full display for the public to witness the atrocity for themselves.

Once I arrived, I parked my motorbike at a safe distance, and I began walking towards the cemetery. I certainly wasn’t a public figure at the time, and I had spent my entire adult life outside of the country, so there was virtually no chance of anyone recognizing me. And, of course, I had nothing to hide. In my mind, I was not a part of the “system” that had led to this violent death, but was rather an outsider, trying my best to change the rotten established order in whatever small way I could.

It took some time to navigate through the rioting masses, bounced around by the pushing and shoving of agitated protestors, while their shouts, along with the cries of grieving family members rang loudly in my ears, but, eventually I arrived at the body. I spent as much time there as the situation permitted, observing the wounds, and finding myself thinking of the countless individuals who had entered my court room with stories of how they had been beaten and tortured by security forces while in prison. They, I realized, were actually the lucky ones. At least they were still alive. This young man had been robbed of his life. Robbed of his future. Even in death it was evident that he had been a healthy, strongly-built young person and I recoiled thinking of the number of blows it must have taken before he succumbed to his injuries. His name was Ivan Naseem and was only 19 years old.

While I was at the cemetery, I happened across Mr. Ahmed Mueez, the first western-educated lawyer to head the criminal court, who had also been my senior at the International Islamic University. He had also come to witness the atrocities committed by the security forces firsthand.

As I returned to my motorbike, I spent a few minutes observing the anger and frustration emanating from the crowd that had gathered. Most importantly, I saw the faces of the young people who had assembled to protest. At the time, it was unprecedented in the country to see such a public display of venting frustration at the authorities. It felt like a watershed moment, and one that could not be quelled or suppressed by the traditional tactics of force that had led us to this very point.

After returning to my office, I gathered all of the judges to recount what I had just witnessed. I insisted that each of them make their own pilgrimage to the cemetery to see how the authorities had beaten a perfectly healthy young man to death. And yet, I doubt any of them actually went. Deep down, they all believed that they were inextricably linked to the “system,” and their natural inclination was to defend it. Expressing any views to the contrary would simply harm their career prospects. They saw me as nothing more than an agitator. A misfit.

The following morning, there was more bad news. The prison inmates rioted, and security forces opened fire, killing a handful of prisoners while wounding dozens more. The public, already agitated by Ivan Naseem’s untimely death, took to the streets and erupted in protest. The government, drawing on recent experience, flew all of the injured to neighbouring Sri Lanka for treatment.

In response, the President established a Presidential Commission to investigate these two incidents, demanding recommended actions to avoid such tragedy in the future.

As it so happened, shortly before this all transpired, I had begun the process of writing a detailed report on the status of the country’s criminal justice system, its challenges, and my proposed solutions. In light of these two incidents, I decided to expedite the report. I hatched a plan: once the report was complete, I would try to secure a meeting with the President to present my findings and recommendations to him directly. My boss, the Justice Minister, had limited power to reform the system, and there was nothing in the report that he would not already know himself. It seemed reasonable then to bypass him in an effort to gain access to the executive of the country, and the individual most likely to be in a position to implement change.

And so, I did just that. Once the report was completed, I requested an appointment with the President. Alas, I received no response. My assumption was that he was too busy with his presidential campaign, actively seeking a 6th presidential term after having already served 25 years in office!

His campaign ramped up shortly after Ivan Naseem’s death and the accompanying prison shooting. And as the days, then weeks, then months passed, the public seemed to have forgotten about young Ivan, the prison riots, and the deaths that ensued.

The Justice Minister encouraged all of the judges to attend campaign gatherings being hosted in the capital, though he instead described them as “social gatherings” rather than political events! As you might expect, I outright rejected the entire façade as nonsense, and privately urged fellow judges to avoid any such events. But, it was all for naught, as my colleagues adhered to the wishes of the Minister, their real boss.

When Election Day came, I opted not to vote. There was no point. President Gayyoom’s name was the only one on the ballot. When the inevitable results were confirmed, long lines formed around the Presidential Palace, which was a mere 100 feet away from our court room. Government officials, titans of businesses, and the public convened to congratulate the President, and wish him success during his new term in office. Nearly all of the judges joined these queues, blurring the line between the executive and the judiciary. It is possible I was the sole judge who chose not to attend!

So, you can imagine my surprise then when I received a call from the President’s Office, informing me that the President himself wished to see me. When I arrived, I was told I would have only 10 minutes. With that deadline in mind, immediately after obligatory greetings, I launched into a briefing of my report on the criminal justice system. President Gayyoom listened intently for several minutes before stopping me. He then explained that this meeting had actually been at his request, not to hear my report, but rather to offer me the position of Attorney General in his cabinet. I was stunned, completely taken by surprise. I thanked the President for his offer, and gladly and gratefully accepted. There was a caveat, however. I made clear that should a time come when I felt I was unable to discharge my duties, I would depart in good conscience.

I was asked to keep this news to just myself and my wife until the formal announcement was made.

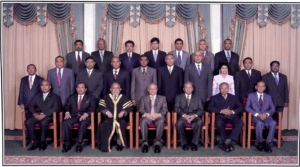

On November 11, 2003, President Gayyoom took his oath of office before the Speaker of Parliament, who also happened to be a senior cabinet minister, as well as his elder brother. Shortly thereafter, Cabinet appointments were announced. I, along with 21 other cabinet ministers, took our oath of office in the presence of the President. Of the entire cabinet, I was the sole fresh face. The remainder of the positions were filled with family members, friends, and old guards and loyalist.

And while I remained honored to have been selected, it was clear the President was not seeking reform. The thinly veiled message was apparent; it would be business as usual.

Not long after my appointment as Attorney General, the Presidential Commission that had been set up to investigate the death of Ivan Naseem and the prison riots submitted its report (on 10th December 2003). Only select excerpts of the findings were ever made public. As the country’s chief legal advisor, it was my jurisdiction to decide what actions should be taken based on the report, and I opted to charge those who were directly responsible, along with the senior officials who could have or would have prevented those events, had they obediently discharged their legal duty.

And while my actions could not bring back the deceased, for a brief moment, I felt as though justice had finally prevailed. I found myself reflecting on that walk to the cemetery, witnessing all of the emotion and pain of my fellow countrymen and women, and I recommitted to continuing my work to upholding the rule of law, using justice as both a deterrent and a tool of accountability, in hopes Ivan Naseem’s memory would not be in vain.