I was born in 1970 and spent my formative years on the island of Feydhoo. My family lived in one of the old British built houses. The accommodation was meagre for a growing family. My mum, dad, four brothers, and two sisters all shared one room, I was the second youngest. We had no electricity, clean water, sewerage system, medical doctor, or even proper schools.

Our family home was a happy and lively place despite the lack of very basic amenities. As you might expect, living in very cramped quarters with a large family wasn’t easy, but we kept ourselves entertained thanks to one of my energetic siblings.

Like any other Maldivian, my earliest memories are of the sea; I recall friends showing me how to fish, casting from the beach. Although I didn’t have a proper board, I loved the idea of bodyboarding, To make my own, I had to improvise, so I created a custom made body board from a plank of wood left over from the neighbor’s house repairs.

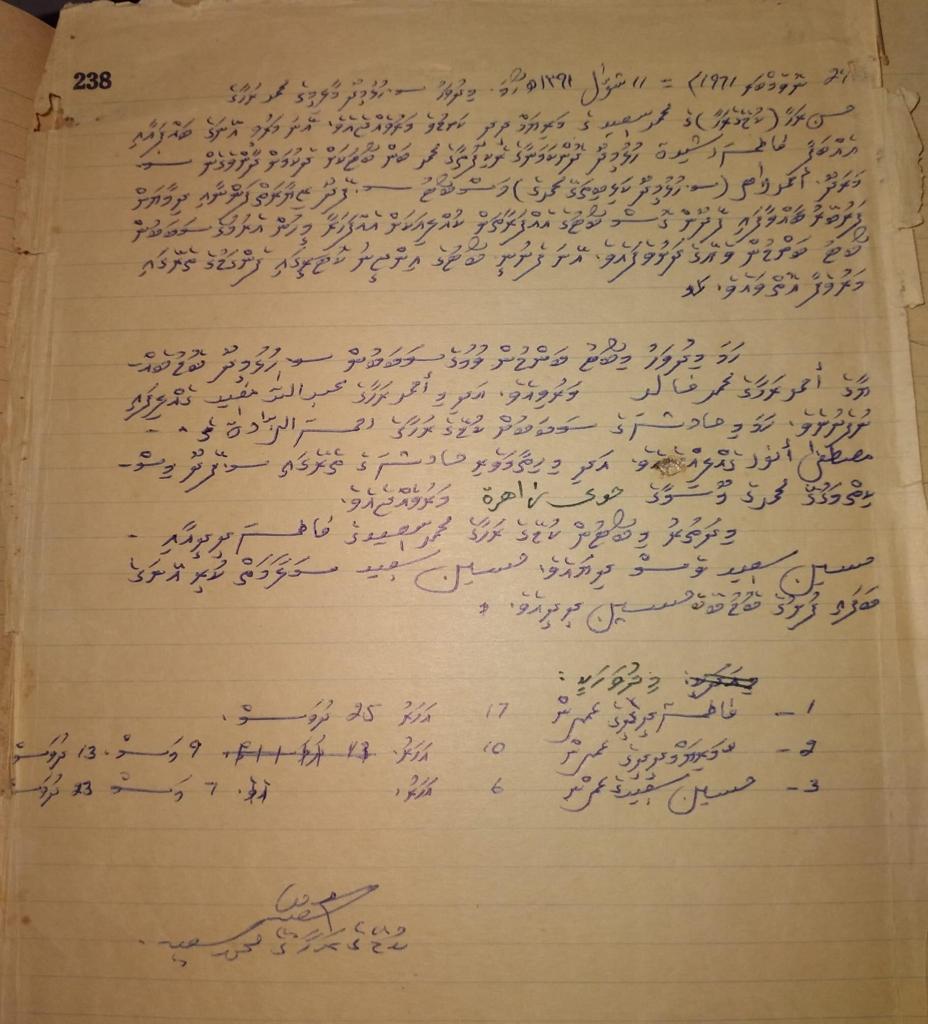

My memories of the sea are a bittersweet mix. Sweet, because of my carefree memories of playing and having fun on the local beaches, but bitter, because it was also the source of tragedy for our family, on 29th November 1971, when a boat carrying a group Island picknickers, including my two sisters (Fathimath Didi 17 years and Mariam Didi 10 years and my brother Hussein Saeed 6) capsized. Twenty people died in the incident, including my sister Mariam Didi. It left a lasting impact on the family.

My father served in the British Army as a waiter and kitchenhand. He was a voracious reader who spent all of his spare cash on books. He taught himself English, Arabic, and Urdu, and was a Reader’s Digest and serialized encyclopedia subscriber. He became a role model for the men on the island, admiring him for his moral character. He instilled morals in his children from an early age, especially when it came to managing money responsibly.

When we were kids, we used to fall asleep to the sound of father’s authoritative but empathetic voice giving visitors advice.

His passion for learning played a central part in our own lives, but not until after tragedy struck again.

My father died in 1978. Due to the island and the country’s limited medical resources, his condition went undiagnosed and rapidly worsened. My mother had no choice but to raise her children alone. It was a tall order, but she did her best, supplementing our diet with extra money earned by cooking for public holidays and festivities. However, without my father to keep us in check, my brothers and I got ourselves into plenty of scrapes and were more likely to become ‘tear-aways.’

Fortunately, before father’s death, he had saved enough money to send his eldest son, Abdullah Saeed (now a professor at University of Melbourne), away to Pakistan to get an education. Abdullah later he obtained a scholarship at Madina University, Saudi Arabia and saved money to send home to pay for his younger brothers’ education in Pakistan. His continued support, guidance, and oversight continue to be instrumental in my educational and professional life. I owe him so much.

It was a hard decision for our mother to let us pursue our educational interests in Pakistan, but she too saw the value of learning and was worried about what would happen without the proper guidance. When I arrived in Pakistan, I was merely 10 years of age. I found learning easy – something that I very likely inherited from my father.

Haaji Abad (in Faisal Abaad, Pakistan) could not have been more different to my hometown in Feydhoo. Nine students shared one tiny room. We had two meals a day – 2 Naan and Dhaal curry for morning breakfast and 2 Naan and One curry (often vegetable or beef or lamb) for dinner. The only time we got fish and Biriyani were during Eid holiday! Otherwise, meals were very much set. It never changed during my 6 years stay at Salafia.

At the time, the Madarasa had a large number of Maldivian students from middle-class families. They frequently received letters and parcels from the post. I didn’t think about receiving postal packages or money from family because I was one of the poorest students. It was simply out of my reach. A rare letter from home from a family member from a good friend was just as satisfying to me.

The most difficult aspect of living in Pakistan was the lack of heating systems and hot water! Imagine taking cold showers in the dead of winter, when the temperature was close to zero! However, we had no choice and did it on a daily basis, much to the surprise of our Pakistani friends. We Maldivian students had a reputation for having high quality hygiene standards.

The ultimate goal of all Madaras students was to be accepted by any of Saudi Arabia’s religious institutions. I was offered a scholarship but turned it down because I was more interested in obtaining a western-style education. Nothing seemed incompatible between western and eastern systems to me. To begin my journey toward obtaining a western education, I studied English with the assistance of my roommates and friends.

One thing that struck me about Pakistan at the time, and has stayed with me, was how dissent was tolerated even under a military dictatorship. It was common to see colorful protests, hear people in the streets criticizing the government, or read a variety of opinions in the press. In my opinion, this atmosphere of free expression was healthy and promoted civic awareness. When Benazir Bhutto (later Prime Minister) returned to the country in 1987, I was there. I, too, was caught up in the excitement, but also in the sense of danger that surrounded her. I was a rebel in my own right. I would encourage other students to join me in refusing some of the more menial work at Madarasa, which I consider exploitative, though it may have also served as an excuse to watch cricket! We didn’t have televisions in our rooms, of course. Instead, we had to sneak out of the dorms to watch the cricket in the local coffee shops. That worked well until the business owner gave us ‘marching orders’.

I applied to and was accepted to the International Islamic University of Malaysia in order to broaden my education. I recognized that without funding, the next few years would be difficult. I bought a one-way ticket to Kuala Lumpur with borrowed money from friends and still had $100 in my pocket when I arrived in Malaysia. When I arrived, I was fortunate enough to receive a grant from the World Islamic Call Society. However, this was insufficient. It was only 150 Malaysian Ringgit per month (about $20) and was barely enough to cover for my food, let alone books and other supplies for my studies.

Later I was able to secure the University and the Government of Maldives’ scholarship award. I now slept in a spacious dormitory with 16 other students. The beds didn’t even touch each other. The dorm was not far away from a five star hotel, in comparison to the dorm at Madrasa, It took some time for me to adjust to university life. I needed to master the English language before I could begin my studies. I read and reread English newspapers and used an English-Urdu dictionary.

It took a lot of perseverance and hard work for me to understand an English newspaper from cover to cover. This intense period of reading, combined with my subsequent studies, contributed to my deteriorating eye condition.

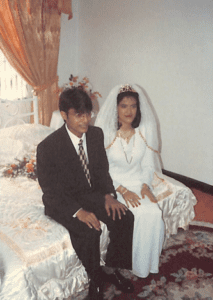

I thrived at university by immersing myself in my studies. I excelled in class and practically lived in the library, frequently reading books and magazines unrelated to my course. Fatin, my future wife, and I met in the library. She was a hardworking student, just like me. Four years later, we married.

After completing my master’s degree in comparative law, I returned to the Maldives to work as a state attorney at the Attorney General’s Office. I had been back twice before, just for short trips, and on each occasion, I was struck by the dramatic changes at home. Most noticeable was the spectacular pace of development. I had left my island Feydhoo by boat reaching the capital Male’ in three days and three nights but returned to the Island by an hour and thirty minute flight. The paved streets and new high raise buildings of the capital were impressive, as was the introduction of electricity and proper schooling to Feydhoo. Yet at work, I noticed that, at least in terms of the legal system, the Maldives was not moving fast enough. I was astounded to learn of the incredibly high conviction rate. The public was led to believe that this was a sign of the court’s efficiency, but this was far from the truth. Rather, it was a reflection of the court’s culture, with judges convicting even when there was insufficient evidence for fear of losing their jobs. For the first time, I became aware of the government’s all-encompassing influence in the legal system. As a state attorney, all I could do was try to persuade the judges I knew to follow the evidence in each case rather than top-down dictates (actual or perceived).

In 1998, I jumped at the chance to complete my PhD in Queensland, Australia, believing that it would increase my influence at home and allow me to contribute more effectively to the system. My wife Fatin was awarded a Malaysian government scholarship to pursue her own Ph.D. Initially, I came with her on a dependent visa. It was once again difficult to fund my studies. I had to work this time. At first I struggled to find work. After completing a professional hospitality course, I found employment as a kitchen hand and served food in a variety of restaurants.

I later worked as a research assistant at the University of Melbourne and a tutor and a lecturer at the University of Queensland before receiving a partial scholarship from the University. But the bulk of income came from the funding Fatin received from the Malaysian government.

On completing my studies in 2002, I immediately wrote a letter to President Gayyoom offering my services. To my astonishment, the President called me to thank me for my offer and invited me to join the government. I told the President that the government will need to pay for my accommodation as rent in the Capital Male’ then and even now remains several times higher than average civil servant’s salary.

My reasons were simple– I wanted to focus on one job rather than multiple jobs, avoid being beholden to the wealthy, or relying on people for favors. The President agreed and honored his commitment till the day I resigned from his Cabinet. I am grateful to this day.

Moving from Malaysia to Male’ was hard. Fatin and I were living on her tutor’s meager salary. Back then, I simply didn’t have money. Two close friends helped me – Mr. Hassan Zareer and Mohamed Shaweed. The former was a few years my senior. We studied together in Pakistan and Malaysia, and I always thought of him as an older brother. Shaweed was a cheerful young man whom I befriended while studying in Malaysia. I am extremely grateful for their assistance.

I started my new life in the Maldives with the role as the Chief Judge of the Criminal Court and the Juvenile Court. A few months later Fatin also came to Male, but not before some negotiation with her employer, the Malaysian Government. The funding she received was conditional on her teaching on her return.We were unwilling to be parted again, so we had to agree to pay back the money. I received several offers of support from Maldivian businesspeople but felt it unwise to owe favors. We negotiated an arrangement with the Malaysian government to pay back the money monthly, a commitment we only managed to complete in 2017.

My new role in the Maldives was as the Chief Judge of the Criminal Court and the Juvenile Court allowed me much more scope to change the system. I wasted no time.

One of my first discoveries was that 97% of prosecutions and convictions were secured on the evidence of a confession alone. Many defendants complained that confessions were obtained through beatings and intimidation. Furthermore, defendants who attempted to retract confessions were charged with perjury.

I started to compile information where prisoner abuse was suspected or alleged. The same police officers’ names recurred repeatedly, under the same circumstances using the same methods. The evidence was damning.

This was far from the only problem in the legal system. There were no rules of disclosure, rights to legal representation, no guidance on appropriate sentencing. I pushed for reform in all these areas, with significant achievement, but all too often I was met with resistance. I was told repeatedly that this was the way things were done. The higher officials did not want change.

I compiled a report on the problems with the country’s criminal justice system and obtained an appointment with President Maumoon Gayoom, agitated by the slow pace of progress. The President only listened to me for five minutes before asking me to be the new Attorney General. The President had scheduled the appointment to offer me the new job, not to hear what I had to say. I agreed, but made it clear that I would only stay on as long as I felt I could perform my duties without interference. The president had no idea what he was doing by giving me this influential position.

My mother died around this time, just before I was appointed Attorney General. Although I was deeply affected by this additional loss in the family, I could only take a brief break from my work.

When I started in my new position, I immediately began a process of reforming both the legal system and a broader program aimed at developing a culture of fairness before the law and democracy. The right to legal representation, evidence disclosure, court rules, the bail system, habeas corpus, and confession retraction were all quickly changed. This was only the start of my ambition with a lot more to come. I felt that because so much of the system was broken, changing things piecemeal was insufficient, and that a more radical approach was required.

At the time, there was a growing movement among the people and within certain areas of government to make radical changes in the state in order to make it more open and democratic. This was very much in line with my own agenda, and I quickly found allies in figures such as the then-Foreign Minister, Dr. Ahmed Shaheed, Information Minister, Mr. Mohamed Nasheed, and my old friend, Dr. Mohammed Jameel, the then-Justice Minister. Others and we formed a government group called New Maldives to push a reform agenda.

The Maldivian Democratic Party (“MDP”) and other opposition groups were also pushing for change, but I was wary of their calls for a violent overthrow of the president and the damaging call for an international boycott of the tourist industry. Moves like these had, I felt, catastrophic potential for a nation that relies on tourism, international reputation and imported goods. While their intentions were good, their policies were shortsighted.

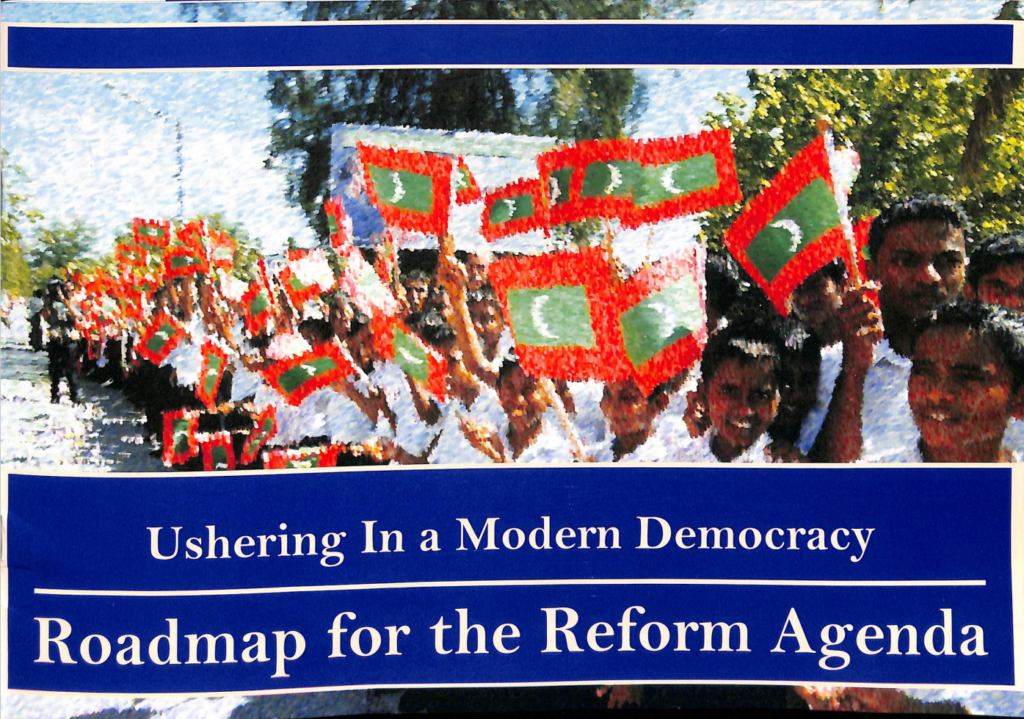

With the release of the Roadmap to Democracy in 2006, the New Maldives movement had a clear agenda, and as Attorney General I made significant progress along that road. This included the introduction of political parties, ending the persecution of writers and reporters, and putting steps in place to strengthen the independence of the judiciary.

However, as time went by it became increasingly apparent to me that, while appearing to endorse the reform progress in public, President Gayoom himself was behind endless moves to block it.

These moves included refusing to replace top police leadership and the inept Chief Justice, impeding the progress of investigations into corruption and illegal activities in government, stalling the Roadmap for Democracy, and addressing religious extremism.

Things finally came to a head in August 2007, when, as I had promised from the start, I resigned from government because I was no longer able to carry out my duties without interference. I was the first Cabinet Minister ever to resign on policy differences with the President and hold a press conference to explain the decision.

It had become clear to me that I had accomplished everything I could in office. The main impediment to reform was none other than the President himself. I realized that in order to achieve true fairness and democracy, a new leadership needed to be appointed.

I decided to run for president in 2008 because I believed that not only was a change needed, but that it needed to be a meaningful change that reached all corners of our society and was implemented by a team that knew how to achieve it.

I, like many Maldivians, had a tough childhood filled with adversity, and I knew the problems that the people of this country faced trying to get ahead. I worked hard to get to where I was in life, not through privilege or cronyism or family connections. In my life it was being provided with the opportunity to succeed that made the difference, and I believed that all Maldivians have the same right to such an opportunity.

In the Madrasa, and later, I learnt the value of true faith. As someone familiar with Islamic scholarly work and a true believer, not just an empty figurehead, I believed that I could and would bring true Islamic Democracy for the country to be proud of, as an example to the world.

As a known reformer, who had achieved real change in my time in office, and as a man of principle who left when that change became impossible, I believed that I could be trusted to deliver the fair society Maldivians and others deserve.

As a young man, with experience of governance, I was both progressive, forward looking and stable, safe, and aware of the unique needs of the country and its people.

I was not in debt to big business, had no relatives in politics, and was not a member of a political party. Unlike Gayoom and other politicians, I was not tainted by corruption or suspicious connections and I had no hidden agenda. The only people I was beholden to are the Maldivian people.

I finished third in the election. President Gayyoom and Nasheed of the MDP advanced to the second round of voting. At this point, I backed Nasheed and assisted him in becoming the country’s first democratically elected President. He named me his Special Advisor. However, he never took any of my advice.

I resigned when Nasheed started democratic reversals. When he resigned in 2012 and his successor Dr. Waheed (who was Nasheed’s Deputy then) appointed me as the Special Advisor. I was able to play very important roles with far reaching political economic and geopolitical consequences [details to be discussed later].

In the 2013th Presidential election, I collaborated with the Honourble Qasim Ibrahim and fell barely 2000 votes short to qualify for the 2nd round of election. President Yamin went on to beat President Nasheed.

I left politics shortly after that and have avoided politics and politicians ever since. I intend to write a historical account of events I witnessed on this blog.